The Healing Land

This essay is based on my revelations while reading the book, Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage by Dianne D. Glave

"She picked up her suitcase with her right hand, held her pumps by the heels in her left hand, breathed deeply, and stepped into the red mud. Her manicured feet sunk into the moistened dirt, soiling the Come Hither pink polish. With each step, memories of her childhood came flooding back. The unfamiliarity of being barefoot in the mud was replaced with sentimentality as she walked to the house, splashing mud about her ankles. Her city strut disappeared and her country girl flat foot stride returned."

That excerpt is from a work in progress titled, 'CottonSack Divas'. More than likely, it will be a novel but for now, it's a few pages of a story that begins with a woman named Sultry Ann Winters. She was born and raised in Mississippi but left after college to live and work in the cities of New York and Chicago. Of course, she returns home for reasons I won't state here because I need to keep something to myself about a work in progress. But this backstory for Sultry is not exactly original. It is the story of millions of Black Southerners. Currently, a docuseries by Henry Louis Gates is being aired on the Great Migration. At the same time, some reports have stated that Black people are exiting major urban centers elsewhere and returning to the South, where over fifty percent of African Americans continue to reside.

The South for African Americans carries a tormented legacy. On the one hand, the South is peppered with metropolitan areas but there is a countryfied realness entrenched in the cultural atmosphere of cities such as Memphis, Little Rock, New Orleans, Nashville, Birmingham, Dallas, Houston, and of course, Atlanta. With a lexicon of phrases spoken with a drawl, the spirit of the South lingers in the breeze as magnolia blossoms sway. It is the region of blues power, Black power, sweet tea, cornbread, and collard greens. It is the landscape of cotton fields and long winding highways with overgrown trees crowded along the margins. Dirt roads that seemingly lead nowhere take you into small communities filled with kinfolk residing within a stone's throw of each other. It is the presence of antebellum homes which were formerly plantation houses; some have been rebranded as Bed and Breakfasts.

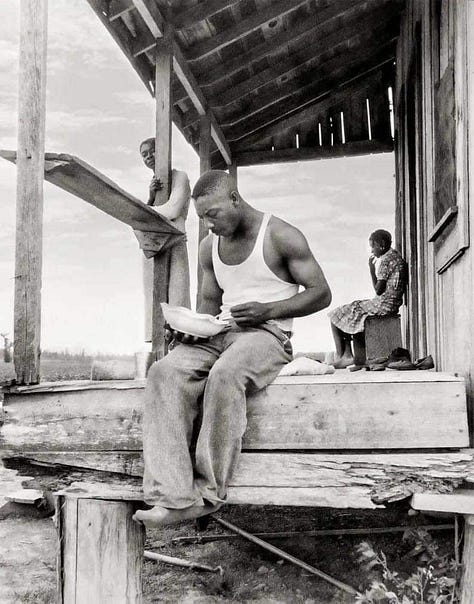

The commonality holding this definition of the South intact is the land, but the land is part of a tense relationship with African Americans. The land was a haunting reminder of broken bodies and uncompensated toiling; along those byways of the region are trace amounts of Black skin and blood, possibly on trees or on the side of rotting buildings that once held importance in the work lives of the People as they produced cotton, tobacco, sugarcane and other crops. It is evidence of an existence that once regarded the working of the land as a poverty-ridden servitude for them and a generational wealth-building machine for white landowners. The Great Migration became a way for many to divorce the strenuous labor of sharecropping and court blue-collar jobs at manufacturing facilities 'up North'. The labor was just as intensive but it wasn't as demeaning and reminiscent of the days of tenant farming and bondage for them. Yet, in the movement of their bodies away from the land, a precious expertise dwindled away, much to our detriment today.

In the book, Rooted in the Earth: Reclaiming the African American Environmental Heritage, author Dianne D. Glave revises the ancestral perception of struggle and subjugation associated with the land and empowers the People by centralizing the agricultural wisdom acquired in the cultivation of crops and the management of natural resources. In my reading of this book, I marveled at the research and deeper thinking that Glave effortlessly sealed into the pages of the text as she covered all aspects of the connections between Black people and nature. Secondly, Glave's purpose was to debunk stereotypes of Black people as beasts of burdens, dumb farmhands or lowly seamen. Instead, she theorized eloquently about the critical knowledge necessary to husband the land, command the seas, and develop conservation practices to ensure that harvest seasons would prosper. This book is documented praise for unsung People and necessary for those of us as descendants who are attempting to reconcile the past.

I swelled with pride while reading this book. It unlocked memories of my life growing up in Mississippi. I recalled my own ancestral lineage; being only two generations away from sharecropping on both sides of my family. I thought of the bevy of plants, one of which was an aloe vera plant, on my great-grandmother's porch and the small but mighty garden she kept in front of her house. The garden was a collaborative effort between her and a neighbor who stayed across that open field. During the winter, our bellies were full because my great-grandmother put countless Ziploc bags filled with the garden's currency in the freezer on her back porch. My granny in Alabama did the same with her garden which also grew fresh peppers and both of them had a chicken shack for fresh eggs.

My paternal uncles used to go fishing and hunting in the woods. Fresh fish and deer meat were their prime targets and often they would bring back prized catches; buckets of fish and a deer ready for prepping. This way of living was so ingrained in their bones. However, that way of earthing wasn't passed down to me and it was intentional. My parents' expectations for me were to attend college, get a degree, a good job and sustain myself so I wouldn't have to live 'the old way'. For them, that would be considered a regression. But now, I see, despite how well-meaning they were, I missed out on a wealth of knowledge about growing my own food, which appears to be a growing necessity these days. But, there is an initiative in the works to reclaim this heritage of mine.

Just as many African Americans are returning to the land of our foremothers and forefathers in the South, we are coming back perhaps more skilled and educated, but definitely not as self-sustaining as we should be. Unlike metropolitan areas, the South still has land to be honored and tended. Land ownership in the rural counties of the South will be a step towards reconciling a torrid history. It can also serve as a recompense for many ancestors whose land was illegally stolen away.

There is a growing movement of African American homesteaders who are finding a special kind of peace in putting their hands to the Earth and willing it to garner sustenance. It seems as though we are still striving for that promised forty acres and a mule. In addition, an increase in Black nature lovers signal a shift from the perception our ancestors justifiably had with the land. Connection is desired now which will allow us to see the full beauty of Mother Earth without the burden of laboring but instead a healing of our lineages and redemption of our collective historical legacy.

So, back to Sultry's barefoot walk in the mud. After decades of a chase for better living in the concrete jungles, many of us are hearing a call to return home -- to drop the pretenses, the demanding aspects of city living and find ourselves in a loving involvement with our ancestors' ways minus the pain. May our walk back grace us richly as we allow the land to heal us. We deserve it and it is time.

Bless the Sweat. Bless the Blood. Bless the Dirt. Bless the Healing. Amen.

Chandra Kamaria is a writer, educator, public scholar and entrepreneur. To support her work, consider becoming a paid subscriber to The Literary Lightworker. You may also contribute by clicking this link: BuyMeACoffee

You have great insight, this was a very interesting and necessary piece.

Beautiful ✌🏻