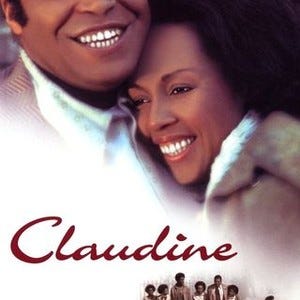

Inspired By: Claudine (1974)

This film celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. As relevant today as it was back then, we can gain some valuable insights about our present day reality. This is Part I of a two part series.

Author’s Note: I started this piece before the legendary James Earl Jones passed away. That’s how long it’s been in the hopper or my drafts. Since that time, the Apollo Theater held a 50th anniversary screening of the film which increased the urgency of publishing this piece.

I’ve been wanting to write about this film for awhile now. It’s one of my favorite movies because the Queen Diahann Carroll and the King James Earl Jones were costars and brought to life a story with more depth than the film was able to convey. As a brief recap, the film is about an African American single mother of six children, Claudine Price, who was living in a Harlem housing project and on welfare. She worked part time in a well-to-do neighborhood for a white family which calls to memory the legacy of Black domestic workers in wealthy white households leading back to chattel slavery, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era. Clearly, she is familiar with the love interest in the film, an African American garbage man, Rupert B. Marshall (aka Roop), as he mentioned on his route one day that he had been ‘studying to ask her out’. After initially declining his offer but giving in once he slightly pressured her with revealing that she’s working on the side while on welfare, she accepts his dinner invitation.

While this film was labeled as a romantic comedy, I consider it to be much more dramatic in its portrayal of how Black living has been and continues to be overly complicated in this nation under legalized oppression. There were some parts of the film that offered moments of brevity in that ‘70s cultural motif, mostly when Roop interacted with Claudine’s children. Despite the film itself being a work of fiction, the situation of single Black mothers prior, during, and beyond the 1970s is not and addressed some specific aspects as it pertains to the values of the Black community in contrast to systemic oppression.

For Claudine, those welfare payments can only cover a few meager expenses and feed her children who are all cramped in a two bedroom apartment. If the ‘welfare folks’ found out that she was secretly working to supplement her income, they would cut her benefits thus causing a greater financial burden. Once Roop entered the picture, their romance is hindered because if Claudine is receiving any assistance from him, they would discontinue her welfare benefits as the program intended on a man taking on the financial responsibilities of the household. These stipulations required Claudine to hide basic convenient appliances such as a toaster and an iron whenever she is being visited by Miss Kabak, the social worker who conducts fidelity checks for the welfare program.

Sensuality vs. Sexual Stereotypes

At first, Claudine’s date with Roop was a bust because Claudine arrived home late only to find her home in full chaos mode. Children were scrambling, the unattended toaster was burning bread, Charles, her oldest son, was taking too long in the bathroom, and all of them were complaining about something as she shouted directives and tried to keep herself from cussing. Roop insisted on the date and took her to his apartment to freshen up before going out. An exhausted Claudine fell asleep in the bathtub and the budding couple opted for a night in with takeout from a fried chicken joint.

During their conversation, the both of them called out the societal depictions of Black women as baby making machines and Black men as the studs who knock them up and flee, forcing the mothers to depend on governmental assistance to take care of their children. Given that this stereotype has its roots in slavery when breeding farms were normalized to increase the numbers of enslaved ancestors after slave ships were banned, it continued to paint Black men and women as sexually irresponsible and immoral. Despite the friction, Claudine and Roop eventually revealed that they have had more trouble with trying to maintain a healthy, fulfilling relationship rather than being promiscuous. Claudine mentioned that she’s had two marriages and two almost marriages, while Roop stated that he’s been divorced twice with three children himself.

Once this small riff is resolved, they laid down with each other; and yes, this is their first date. Sidenote: I really do love the phrase ‘lay down with each other’ when referring to making love. It’s indeed old-fashioned and genteel, but it brings forth such an intimate and sensual image for me. Throughout the film, we find Claudine and Roop oftentimes naked and in bed. Their relationship seemingly had a sensual undertone to it and ain’t nothing wrong with that as lovemaking is an integral part of a romantic relationship.

“Keep Away from Him…Mr. Welfare”

Roop and Claudine weren’t able to be a fully committed couple, initially. At some point, Claudine started developing feelings for Roop but her family life prohibited her to be starry-eyed about their sexy situation. Coupled with her past experiences, Claudine wasn’t sure if the relationship with Roop could go the distance. For one, she had a warped view of love herself when she tells her daughter, Patrice, in one scene that ‘love is a man bringing the groceries instead of eating yours'. This added another inference into her past, which suggested those previous marriages and relationships were not reciprocal.

When sensual desire blossoms within a relationship, it can be a challenge to manage in order to ensure that the relationship is able to withstand its peaks and valleys. If an overextending influence impacts a relationship, being intimate can cause tension. Claudine and Roop, while enjoying their sensual compatibility, had to face the reality that their involvement was imbalanced due to her financial dependency on welfare as well as her kids’ acceptance of his presence in the home. Roop initially liked the idea of being with a woman who he perceived as a bit desperate because she had six children, but then as Claudine started wanting more than just romps in the sack, he was faced with a dilemma to either take on her and her family or continue to support his, albeit from a distance.

A Black woman during Claudine’s time had very little access to education and decent-paying jobs. If they were not married, their financial struggle was complicated even more by not being regarded as an upright woman in the eyes of society; being a single mother meant she had to constantly fight for her dignity. For Black women like Claudine, being on welfare was an embarrassing reality as her life was under constant scrutiny to ensure compliance with the demeaning requirements of welfare policy. Despite this reality, Claudine deserved to have a sincere love in her life but how could this love sustain her, Roop, and her children if their familial roles were compromised by abject poverty?

Roop’s financial wellbeing, seemingly modest at first, became another overarching factor as his wages were garnished for additional child support. If Claudine’s dysfunctional relationship with Mr. Welfare wasn’t enough of a complexity, then definitely a man who was unable to be the breadwinner in the family adds another obstacle. From here, the two lovers had decisions to make. Without providing any more spoilers, this is where Part I ends.

In Part II, I will continue my reflections of the issues highlighted in the film and how those issues have present-day implications for Black living. Meanwhile, enjoy this cinematic gem. During the opening credits, YouTube silences the soul joint, ‘On & On’ by Gladys Knight & the Pips, due to copyright restrictions. But once the dialogue begins, the volume is restored.

Claudine remains one of my all-time favorite films. I was in 9th grade when it came out. It remains relevant in perpetuity.

This is a great read!! I plan to watch this film soon!!